Tags

chawton, frances burney, hampshire, Jane Austen, mansfield park, pride and prejudice, romanticism, southern england, wollstonecraft

“Her own thoughts and reflections were habitually her best companions.” – Austen, Mansfield Park

If you’re sticking with me during this one-month research trip in southern England, chances are you like books and this entry is devoted to some pretty fine and rare books. My brother calls physical books – you know, the pre-Kindle ones made from paper and paste and ink – “dust collectors” but he does so only to irritate me, and succeeds every time! Older brothers are especially skilled at such things. Christopher, are you out there? You didn’t even wish me a bon voyage! Ah well, as Austen writes in Mansfield Park, “What strange creatures brothers are!”

Below are some real jewels found only in the Chawton Library. Wait for them: don’t scroll! Here is the statue of the author herself just in front of Saint Nicholas. I purposefully avoided “Authoress” for reasons that will soon become clear. The bonnet is to Jane Austen as the crusty old beard is to Walt Whitman, or the coke nail to William S. Burroughs.

As I made plain in my original post, my heart really belongs to the radicals of the English Romantic period: Godwin, Paine, Wollstonecraft, Hunt, and the Shelleys. My father would never identify as a hippie – he can’t even whistle a Beatles tune – but he did instill in Meg, Chris, and me a spirited anti-authoritarianism. We weren’t even expected to follow his rules; it was my mum’s job to enforce the rules. (Uh-oh, English colloquialisms creeping in already!) We don’t really know much about Jane Austen’s mum; like most women of the era, she was more pregnant than not and social norms demanded that girls be promptly married. I wonder how much of the marriage-crazed matchmaker existed in Mrs. Cassandra Austen and whether she, in parts, inspired the risible Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. It’s worth noting that when her daughter, Elizabeth, first speaks in the novel, she politely chides her mother for acting the fool. There’s a subtle radicalism in any household where the children know more than their dear ol’ mums and dads. Isn’t Mr. Bennet’s reaction to Elizabeth’s rejection of the man-splaining Mr Collins the best ever? But I digress.

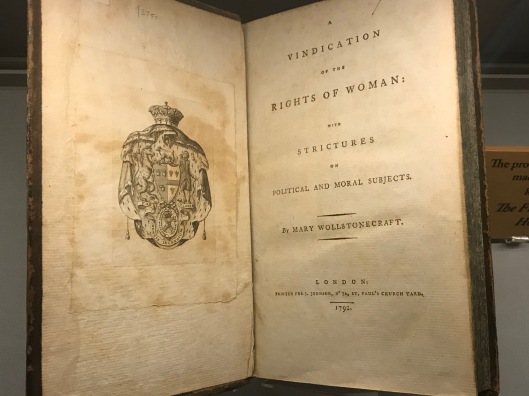

If you are a self-respecting Austenite, you must must must visit and donate generously to Chawton House. You can even sponsor a brick! What’s wonderful about the librarians and curators at there is that they have created a splendid showcase of women writers from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including an original edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (published in 1792). This political manifesto, written hastily in a matter of days, inaugurated the modern feminist movement as we know it, and its central postulate is pretty much a no-brainer (as much as I hate that expression): give girls an education! Reason is the tide that lifts all boats, including husbands who have nothing of substance to talk about with their pretty but empty-headed wives. I use “no-brainer” because, as Wollstonecraft forcefully argues, a brainless woman is also a petty, conniving and coquettish woman. Ridiculed as a “hyena in petticoats” during her day, Wollstonecraft was a true renegade and it’s a tragic irony that she would die in childbirth, leaving this world but leaving behind the motherless child that would go on to pen Frankenstein. (Don’t get me started!) Fun fact: First Lady Melania Trump keeps a copy of A Vindication on her nightstand and longs for her own prison-break. Nah, that’s fake news! The Trumps don’t read! Frederick Douglass is still doing a fantastic job, remember? It’s nice to have a month off from our national nightmare.

Remember from the last post that the Austen sisters lived down the road in a brick cottage but would walk to the great manor house owned by their richer older brother. Creative types are usually idiotic when it comes to money, so Edward’s very existence must have been a family blessing. He was Lord of the Manor of Alton Eastbrook and had a Grand Tour, as was the custom for English men hoping to get frisky on the Continent. As Madonna liked to advertise, Italians do it better, and by “it,” she meant temper tantrums in satin pajamas from Harrods. Edward Austen/Knight was adopted by the Knight family, which, as a new friend at Chawton reminded me today, is a lot like the adoption of Fanny Price by the Bertrams in Mansfield Park. Movin’ on up! Here’s another allusion: Edward would rent, or let out, Chawton much like the line below in the opening paragraphs of Pride and Prejudice (“Have you heard that Netherfield is let at last?”).

The peacock is actually on loan from the Oscar Wilde estate. The proud peacock is a bit “overdetermined” – English lit. crit. talk – but it beats a buzzard or a turkey. Another (American) Romantic, Edgar Alan Poe, reportedly, chose the parrot before he finally settled on the raven, which was a smart move. He made that decision after the opium and incest wore off. Imagine the announcer yelling: Please welcome to the field, the Baltimore Parrots! And the crowd went wild.

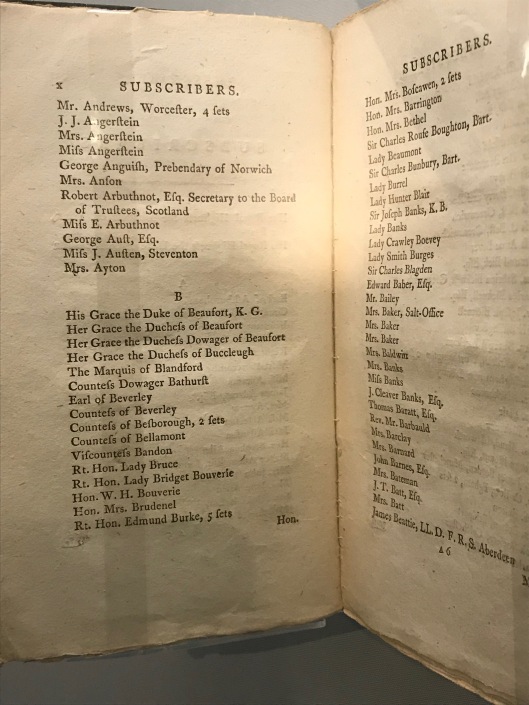

Finally, above is the only time that Jane Austen saw her name in print as she published anonymously, as was the custom for authoresses (too many S’s) of the age. Look on the left-hand side and down ten rows. Dating from 1796 – Austen would have been twenty-one – she is listed as a subscriber to Frances Burney’s Camilla: or a Picture of Youth. “Miss J. Austen, Steventon.” Why put your name on something when the book reviewers at Blackwoods would skewer you even worse for being a “woman writer”? Oh yeah, and a woman who earned a living through writing hadn’t yet emerged yet. Some still maintain, erroneously, that Mary Shelley’s poet husband, Percy Bysshe, wrote Frankenstein and, in its day, the gothic classic was damned as the “foulest toad-stool” to ever spring from a dung-heap. Clearly the reviewer hadn’t read the Twilight series.

Overheard, by the way, by noisy Americans in the pub across from the Jane Austen House: “Since I turned fifty, I have to pee every ten minutes. Maybe I need a sleep study.” Then, the wife (returning with a gift bag from the Jane Austen House and Museum): “Is there only beer here? Austen probably only drank cocktails…more feminine!”

Okay, there are a number of things wrong in this exchange: prostates and sleep do not correlate, and while Austen does complain of a hangover in her letters, there were no Cosmos or Palomas in Regency-era England. Immoderation of any kind is a loathsome thing in Austen’s fiction. A major influence over her was Brunton’s Self-Control (1811). It’s not the booze but how it’s used. This is why the “dangerous illness” of Tom Bertram is singled out toward the conclusion of Mansfield Park. His immoderation inevitable catches up with him; hence: “Tom had gone from London with a party of young men to Newmarket, where a neglected fall, and a good deal of drinking, had brought on a fever.” Fever in the evening, fever all through the night…

Somewhere along the line, “Sex and the City” and Jane “RomCom” Austen embedded themselves in the bloodstream of modern female culture. Yeah, you become a fly on the wall when you’re flying solo in an English village. I’d be even more invisible if I were a lady even though I like to think I’d be a pretty hot chick, bonnet or no bonnet.

In my next post, we will all head to the gardens at Chawton House, so bring your sunscreen!

Wow, Madonna weaves her way into to this post too. Let’s really take a look at the material girl and how she’s an influence!