Tags

ari graynor, Chloë Sevigny, Cooper Koch, crime, Dahmer: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, drama, George Gascón, javier bardem, Kim Kardashian, Menéndez, menendez-brothers, Milli Vanilli, netflix, news, Nicholas Chavez, Rosie O’Donnell, Ryan Murphy, The Assassination of Gianni Versace, true-crime

Blood Brothers

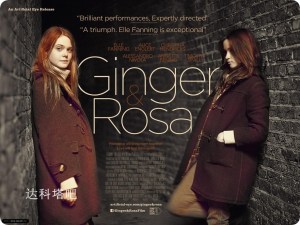

“Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menéndez Story”

(Netflix)

NO OTHER series breaks a beating heart in such an unsettling way than the closing episode of “Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menéndez Story” (the latest delivery by director Ryan Murphy, of “Glee” and “American Horror Story” fame). On his own, Murphy re-sensationalized the craziest legal cases of the 90’s in high-society America: “The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story,” “The Assassination of Gianni Versace,” and “Impeachment” (on the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal). Then, in 2022, with co-creator Ian Brennan, he dabbled in “Dahmer: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story,” which won the titular actor a Golden Globe. For Murphy, it’s seemingly impossible to look back in time without thinking of a dead body, and he makes no apologies that such nostalgia is a vanity affair. “The Menéndez brothers should be sending me flowers,” Murphy boasted to People,“They haven’t had so much attention in 30 years. And it’s gotten the attention of not only this country, but all over the world. There’s sort of an outpouring of interest in their lives and in the case.” Harsh words, and exploitative in their own way. If you already made an attempt to humanize a gay killing-machine like Dahmer, why stop there? The cover art for “Monsters” on your Netflix homepage – the Menéndez bros in an erotic embrace – says it all.

Celebrity gossip aside, the final minutes of “Monsters” go down like vinegar: no catharsis, no resolution. The finale begins with the brothers in their jail cells whereafter they are escorted by armed guards to separate minivans, and when the vehicles divert through an aerial shot, Erik pleads: “I thought we were going to Folsom.” Milli Vanilli’s “I’m Going to Miss You” is playing and the lyrics have taken on a creepy resonance:

“It’s a tragedy for me to see the dream is over/ And I never will forget the day we met / Girl, I’m gonna miss you.” The less stoical Erik begins to cry because he and his brother have been separated. The prison guard could not care less about the inmates’ feelings: “Your brother is going somewhere else.” Case closed. Or is it? Outgoing Los Angeles DA George Gascón has requested new sentences and cited a change in cultural attitudes toward same-sex incest. The tragedy of it all is not only affecting because it’s deeply dark – its eight preceding episodes are even darker – but because it reinforces what the whole Menéndez murder trial represents: the question of human evil, exploitation at the hands of one’s loved ones (especially where primogeniture is at play), and the uncomfortable fact that fraternal incest is a real thing. It’s not a who-done-it – Lyle and Erik confessed to the crime and cried on the stand (later mocked as crocodile tears on “Saturday Night Live”) – but a why they did what they did. The Beverly Hills mansion remains on a sightseeing bus for Hollywood tourists to this day. Apparently, murderers can become quasi-movie stars.

The very subject of fraternal incest still makes GLBTQ+ recoil at the very topic, and the battle of the sexes played itself out in the courtroom: female jurors said “I feel your pain” while males said “Fathers don’t abuse sons, so this is not credible – the so-called “abuse excuse” – though both agreed on life sentences. After 30 years of prison time, “Monsters” renewed re-scrutiny in the case – high-profile defenders such as Kim Kardashian and Rosie O’Donnell have called for their release – and there are thousands of whom found the series intensely moving because queer boys have bullseyes on our backs and are too often targeted by family members. “Monsters” perfectly un-answers the question: what extreme lengths can the victimized be driven – to retail therapy, to sexual masochism, to sexual assault, to murder? – and what, then, qualifies as monstrous behavior. Behind bars, Erik develops a bond with a fellow prison-mate. Erik (played by out actor Cooper Koch) pumps irons, shows off in the shower, and replies defensively to Tony (Brandon Santana) whether he is gay or not: “I don’t even like that word…but I like being around you.”

The episode “The Hurt Man,” a nickname that he gave himself after years of victimhood, is astounding: his defense attorney Lesli Abramson (Ari Graynor) sits with her back to the camera while he details years of abuse; scribbling notes, she says: “[José] was a monster…Lyle feels you had it worse.” The pilot, “Blame it on the Rain,” eases the viewer in with a lavish upbringing à la the grand style of Beverly Hills. The brothers live a life of limousines, bottle service, 25-thousand-dollar tennis lessons (after which they are berated by an irate José), a hard-drinking mother Kitty, and Lyle’s expulsion from Princeton for plagiarism.

Then, in 1989, the Cuban-born music producer and wife were gunned down by their sons while sleeping in front of the TV. They entered from the back. What makes Lyle’s cocky reassurance that his baby brother will perform well at his parents’ wake (“He’s a great actor…He did a Shakespeare monologue once,” he tells a grieving friend) is that it’s all such a charade; only days after the murders, the brothers floated the idea that the mafia was culpable. Lyle (actor Nicholas Chavez) hits play on the song “I’m Going to Miss You” by Milli Vanilli, leaving the grieving parishioners squirming in their pews. What an ingenious song-choice – it closes out the aforesaid finale and in ways that carry on a completely different meaning – as Milli Vanilli had their Grammy award revoked after the public learned the German duo had faked their vocals tracks. In “Spree: Episode 2,” the Menéndez brothers are high on drugs and, bathed in Benneton (an important pastel color that Abramson thought would soften their image in the court of public opinion), nearly French kiss at a house party. From there, there was a cocaine-fueled, Rodeo Drive spending spree that made Madonna look like Mother Teresa.

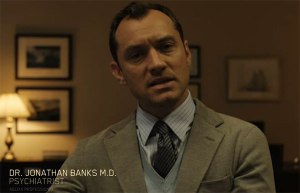

In that last scene, José (Javier Bardem) and Kitty (a chillingly unwarm Chloë Sevigny, as always) are chortling over charcuterie and the great wealth that shark-fishing journey afforded them. In 1989, José Menéndez’s fortune stood at roughly 15 million dollars. Paterfamilias or predator? Only four people know for sure. Adding fuel to the fire is the fact that Edgar Diaz, a member of the boy-band Menudo, has recently confessed that he, too, was abused by José. He and Kitty are all piggish giggles as their sons stand angrily apart. At the bow of their privately chartered boat, the brothers stand with all the vengeful pride and remorse that anyone who has a family knows to the core. Lyle, ever the mastermind and manipulator of what is to come, circles back (just like the 90’s soundtrack, and the cultural nostalgia of it all) to his solemn oath: “I will always choose my brother over my parents.” But who, at the bloody end of this frightening family feud, got fed to the sharks?